Not a Petty Theft: Kleptocracy & American Complicity

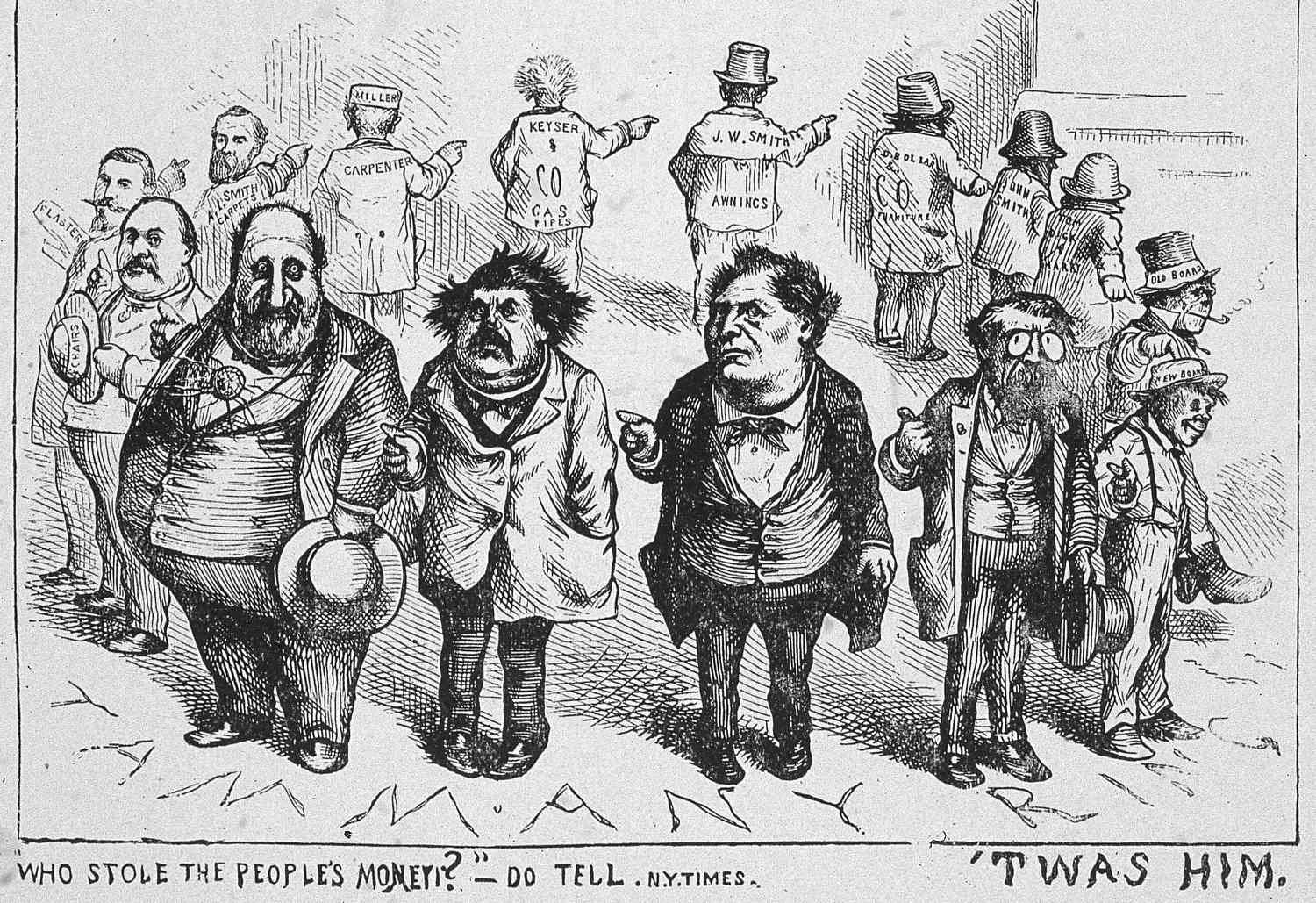

Thomas Nast/New York Times

“Power corrupts and renders its possessors responsible; the possession of wealth liberates and enslaves.” – Kenneth Waltz

American Corruption

Corruption in contemporary American politics–from Representative George Santos’ 23 criminal counts for dubious and illicit campaign finance practices (among his incalculable other fraudulent misrepresentations), to Senator Bob Menendez’s alleged gold bar-for-influence bribery scheme–reflect an ongoing and egregious erosion of democratic rule of law. From the Teapot Dome to Watergate scandals, the American public is no stranger to high-profile corruption. But, much like Justice Potter Stewart’s adage on pornography, we’d like to believe that we know corruption when we see it. Nonetheless, Special Counsel Jack Smith, a former Hague International Court Prosecutor and Chief of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section (PIN), remarks that litigating corruption often has little to do with “what one person did and the other person did. It’s not debated what a politician was given” or the benefits reaped by “the person who gave him something.” Instead, the “battleground in these cases…is what was that person’s intent?” (“Jack Smith | C-SPAN.org” 2011). Although the public often recognizes and rallies against perceived corruption, perpetrators of the crime often take full advantage of complicated legal mechanisms to conceal and obscure the nature of their crimes, making it very difficult for prosecutors to reach the threshold of malign intent.

Kleptocracy

While the Arcadia Political Review has covered corruption previously (see Milla Ghandour (‘23) “Corruption: The Epidemic that Destroyed Lebanon,” or Reed Schwartz (‘24) “Repositioning Admissions’ Side Door”) this article will cover the virulent threat of civic cultures that sanction egregious and grand corruption: kleptocracies. Meaning rule by thieves, kleptocracy was first used colloquially in 1819, but by the middle of the 20th Century became synonymous with the systemic corruption of “the ruling classes of the recently independent ex-colonies” who were perceived, by the rather parochial political scientists of the day, as having no greater loyalty than to their kin’s enrichment (Bullough 2018). An optimally kleptocratic regime provides relative impunity to sanctioned looters–often office-holding oligarchs–while maintaining just enough economic stability to “prevent popular uprising” or leveraging “repressive state security services so that uprisings are quashed” (Mayne 2022). Maximally kleptocratic regimes are a veritable house of cards, effectively a pyramid scheme with politicians on top and their “underlings beneath them, with each layer stealing in turn” (Bullough 2018). Citizens suffer in every “interaction with officials,” having to offer bribes for expected services, as do low-level civil servants whose salaries are extracted by their supervisors (Bullough 2018). As such, these regimes are, at their core, fragile; kleptocrats must maintain their hold on power, placating their citizens and key governmental figures, to ensure their own protection and continued enrichment.

Kleptocracy, when compared to corruption, has an added level of complexity required to maintain these schemes: it is not just to steal and spend, but to obscure both these activities (Bullough 2018). Kleptocrats take extreme measures to obscure the flow of their finances through deceitful practices “limited only by the imagination of the lawyers, bankers, and accountants who do the work” (Bullough 2018). The advent of post-World War II global financial architecture created loopholes ripe for exploitation, only accelerating the pace of financial fraud. The system was established with the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency, and rather than a global currency policed by a global agency (the IMF for example), the U.S. Treasury Department would effectively be tasked with ‘global’ regulation (Bullough 2018). As such, banks in the City of London realized that “if they used dollars outside the United States, then U.S. regulators could not touch them” (Bullough 2018). Thus, the advent of ‘stateless’ dollars ensured difficult to trace, easy to move, currency for those in need, spurring interest in what would become offshore banking practices. Through legal maneuvering, financiers would even come to offer packages such as the Eurobond, a “highly convenient bond that could be turned back into cash anywhere, one that paid a good rate of interest not subject to taxes of any kind,” and existed “outside the jurisdiction of any government; they were the ultimate expression of offshore” (Bullough 2018). Kleptocracies seized on the relative availability of offshore banking schemes, combining their stateless dollars with key instruments such as shell companies with unrecorded ownership information, foundations, and limited partnerships to obscure the nature of their investments (Bullough 2018). While some commentators use kleptocracy to identify egregious state systems with sanctioned corruption, it is no longer just about “whether a particular country is a kleptocracy or not…it is globalized, not confined behind national borders” (Bullough 2018).

Nothing Petty About this Theft

The predation of kleptocratic governments can especially be seen in nations with regime instability. For example, the new military regime in Sudan, led by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) who carried out a 2021 coup that dismantled the civilian-led government, quickly consolidated its power through economic leverage, maintaining a pattern of kleptocracy familiar to Sudan’s modern history. Nonprofit organizations like C4ADS track global kleptocratic networks, especially the mechanisms used to obscure connections between a given state and their state controlled enterprises (SCEs) which are used to evade economic sanctions (Cartier, Kahan, & Zukin, 2022). Their report on Sudan indicates that direct state control of SCEs “decreased from 55.4% to 37.4%–and indirect control increased from 4.5% to 21%” (Cartier, Kahan, & Zukin 2022). What this means is that the new regime simultaneously strengthened state control over major enterprises while concealing their presence through a network of proxies, obscuring their direct ownership to circumvent sanctions. For instance, the SAF maintains a complex charity network, ostensibly a humanitarian investment arm, that it uses to maintain its control over the economy and “insulate the military budget from civilian decision-making” (Cartier, Kahan, & Zukin 2022). Through complicated financial and legal structures, the SAF has seized more than 86.9% ownership of the Omdurman National Bank (ONB), “Sudan’s largest financial institution, valued at more than all other public financial institutions in Sudan combined” (Cartier, Kahan, & Zukin 2022). Illiberal regimes actively leverage the mechanisms of kleptocracy, not just for self-enrichment, but to strengthen the rule of their regime and limit the likelihood of a well-supported opposition movement.

American Kleptopia

The US, both as the global reserve currency and as a major economic powerhouse, has “become the key cog in the machine of modern kleptocracy worldwide, allowing illiberal regimes everywhere to flourish.” (Michel 2020). Not only are American bankers and lawyers, in part, responsible for the advent of early offshore banking schemes, but they enable corrupt officials like “former Ukrainian president Victor Yanukovych,” with the tools to “disguise their ownership of assets with innocuous-looking corporate vehicles.” (Bullough 2018). American states like Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming actively profit off of anonymous shell companies, establishing major company formation industries, which limits the incentive to identify “who may be behind the anonymous shell companies mushrooming across the country.” (Michel 2020) States who willingly participate in “this race to the bottom,” are complicit in frauds perpetrated by global criminals such as the Merchant of Death, Viktor Bout (a now infamous arms dealer) who used “anonymous American shell companies to smuggle missiles and rocket launchers to rebels in Colombia” (Michel 2020). Not only does this erode American national security interests, but it reflects a double standard between outward anti-corruption policies and internal willingness to accept the flow of dirty money, “turning the US into a behemoth in the world of tax havens” (Michel 2020). The U.S. has recently reaffirmed its commitment to target kleptocracy, such as efforts within the G-7 to establish a Russian Elites, Proxies and Oligarchs (REPO) task force, tasked with seizing or freezing the “assets of 50 individuals sanctioned by all eight states, including senior members of the Russian government” (Chong & Tugendhat 2022). Nonetheless, it has simultaneously rejected proposals to strengthen internal controls and regulation. For example, a 2011 proposed exchange of “information on nonresident aliens’ bank accounts with their home countries,” was rejected by “25 members of Congress from Florida (which has particularly high levels of nonresident deposits)” (Bullough 2018).

The U.S.’s complacency, and at times explicit complicity in supporting kleptocratic regimes will only serve to erode democratic values on a global scale. Kleptocratic culture, which begins through the normalization of corruption and the dismantling of civic norms, offers the corrupting incentives of power and self-enrichment. The U.S.’s self-perceived bonafide credentials as a leader in anti-corruption, notwithstanding the few instances of high-profile corruption permeating in the popular consciousness, still stands. Nonetheless, as one of the largest institutional enablers of kleptocracy, the U.S.’s complicity to the spread of kleptocratic culture globally, threatens to infect its largest enabler by, in turn, eroding democratic rule of law and normalizing domestic political corruption.

References

Bullough, Oliver. 2018. “The Rise of Kleptocracy: The Dark Side of Globalization.” Journal of Democracy, January 2018. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-rise-of-kleptocracy-the-dark-side-of-globalization/.

Cartier, Catherine, Eva Kahan, and Isaac Zukin. 2022. “Breaking the Bank: How Military Control of the Economy Obstructs Democracy in Sudan.” C4ADS. C4ADS, 2022. https://c4ads.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/BreakingtheBank-Report.pdf.

Chong, Michael, and Tom Tugendhat. 2022. “The West Must Widen the War on Kleptocracy.” Foreign Policy, April 14, 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/14/democracies-war-on-kleptocracy-russia/.

Mayne, Thomas. 2022. “What Is Kleptocracy and How Does It Work?” Chatham House– International Affairs Think Tank, July 4, 2022. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/07/what-kleptocracy-and-how-does-it-work.

Michel, Casey. 2020. “How the US Became the Center of Global Kleptocracy.” Vox, February 3, 2020. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/2/3/21100092/us-trump-kleptocracy-corruption-tax-havens&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1697587379704759&usg=AOvVaw0ITOBA_vsJQsOYZYWxvBTL.

www.c-span.org. 2011. “Jack Smith | C-SPAN.org.” C-Span, March 25, 2011. https://www.c-span.org/video/?c5042025/jack-smith.