Book Review: Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society

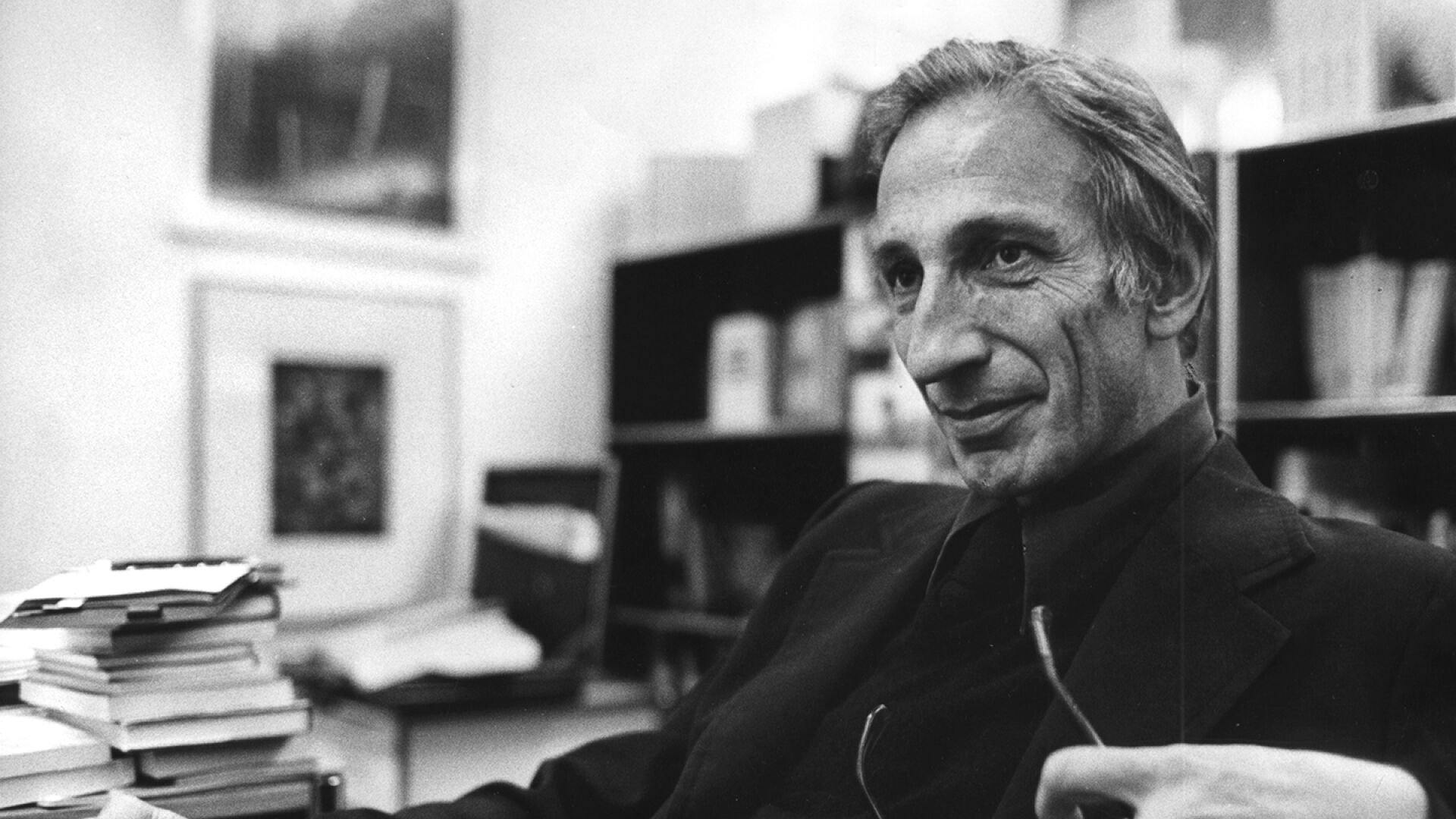

Mondadori/Giorgio Lotti/Getty Images

“If you want to get laid, go to college. If you want an education, go to the library,” goes an apocryphal Frank Zappa quote. Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society elucidates the same idea in 186 pages, in a polemic against formal education and a celebration of organic knowledge. A renounced Austrian priest, Illich was widely read until an impolitic book about gender roles made him persona non grata on the New Left. He remained a close confidant of California’s Governor Jerry Brown until his death in 2002, and his ideas have had remarkable staying power even if his name has not. Still, his ideology grew out of the ‘60s, and though his pedagogical insights remain relevant, his analysis is plagued by the era’s reflexive distrust of the state.

Illich’s deschooling project begins with a deconstruction of childhood. Western childhood is, as he notes, a modern invention: both the insulation of early life from labor and the idea that one is not responsible for themself until adulthood are inventions of the European leisure class. Child labor standards were not implemented federally until the New Deal, and until the Second Vatican Council in the ‘60s, children were told that they were capable of mortal sins (and committing themselves to eternal Hell) at the age of seven. Once these reforms were implemented, they relegated education to the schoolhouse, stunting its natural occurrence in the world. Illich believes that this led to a pedagogical alienation on par with the alienation of labor and unjustly deprived children of agency (Illich notes that Marx opposed laws forbidding child labor, as he didn’t want children robbed of the education provided by production). Suddenly, they could only earn responsibility through years of formal schooling—the system creates its own demand—and academic credentials became prerequisites for engaging with society.

Once modern schooling confined children in formal education, schoolteachers grew into new roles as custodians, moralists, and therapists. As custodian, the teacher drills rote knowledge and polices adherence to arbitrary rules; as moralist, they are expected to instill values in lieu of parents, churches, or the state; and as therapist, they guide the personal growth of a child, “[persuading] the pupil to submit to a domestication of his vision of truth and his sense of what is right” (23). Illich sees in these roles both a violation of the rights of children and a confusion of distinct ends. Students who fail to obey become simultaneously “[outlaws], morally corrupt, and personally worthless”—scholastic failures become personal failures, regardless of their underlying causes (the need to work or a lack of school resources, for example) (24). (This is better explored in Freddie deBoer’s The Cult of Smart.)

What is the purpose of this overreach? Illich sees school as an organ of capitalist high modernism, through which youth are molded into obedient consumers. By discrediting the self-taught, schools delegitimize non-professional activity and further a cargo cult of credentials. Students are socialized to trust elites and achievers, so only those who perform years of conformity are taken seriously in their dissents. They are also taught that values can be quantified and graded, even for immeasurables like emotional growth, and that what is worth learning can only be determined by outside experts.

Illich’s skepticism toward formal structures was not limited to the education system: in Medical Nemesis, he applied the same analysis to professional medicine, accusing it of creating more disease than it cured. However, he was not a reactionary, opposed to all interventions. Rather, he believed in convivial tools that facilitated, rather than organized, social activity.

Illich places modern schools on the right wing of a convivial-to-coercive spectrum. Prisons, the military, and police are similarly right, while networks like the postal service, public transportation, and telephone lines are the furthest left. While coercive institutions force people to behave in ways laid out by the state, convivial institutions allow populations to use them as they wish, meeting local needs without experts and bureaucrats. Institutions can change color as they shift from enabling to commanding. For example, public access roads are convivial, but slide right if they only permit specific vehicle classes. Illich’s project in Deschooling Society is to propose a convivial system of education, one that allows each person to educate themselves rather than having professional teaching forced upon them.

Deschooling begins by empowering children to take charge of their own education. Learning would be built on natural curiosity: even if children are not required to perform actual productive labor, Illich believes that workplaces, factories, and other private and public spaces barred to them should be made safe for observation. The relationship between children and the knowledge they absorb would not remain limited to their own development: Illich suggests that children be granted suffrage at age twelve, when they would contribute to the direction of local government from a unique vantage point. Knowledge generation would be understood as the purview of all members of society, not just an anointed educator class.

Though the state’s role in education would be slashed, Illich does envision a series of government services that would facilitate education. Libraries would be expanded, providing knowledge depositories and reference services that would help people build their own educations for free. In addition, Illich proposes a computerized peer-matching system, which would help learners seek out fellows with whom they could study and exchange insights. (Illich acknowledges the threat that governments could monitor these systems for potential dissidents but says “that this should still worry anybody in 1970 is… amusing,” as there would be no way for intelligence agencies to sort through droves of false positives. This was probably more convincing in the 70s than in 2023.) This dynamic would enable reciprocal knowledge development, allowing learners to act as students as well as teachers, and would skirt the prescriptivism of pre-packaged curriculums. Skill exchanges would be hosted at these reference centers, in which practitioners could teach their crafts in exchange for vouchers. Professional instructors would still have some role to play, but they would be independent rather than attached to institutions, and they would be rewarded based on the number of students they could attract rather than their fealty to an administration or dogma. Access to these independent educators would be free, or paid for with vouchers, with some yearly voucher stipend guaranteed for all.

Illich has faith that once the relations of education are changed, political relations will follow. He relates an anecdote about a fellow traveler, Paulo Freire, who found reciprocal education to inspire political awareness, especially in the developing world. Freire found that the basic literacy taught to tenant farmers in Brazil reverberated in their communities and that they were able to distribute that knowledge on their own terms. Farmers were motivated to learn in order to understand issues like debts owed to patrons, and the mutualist pedagogy inspired solidarity that carried into the political realm.

Distributed education could even boost efficiency: Illich cites an instance in which Hispanophone teenagers in Harlem were recruited to teach the language to a corps of social workers. Their job was completed within six months, radically faster than formal courses. Illich is correct both that 1) personal tutoring is the fastest way to learn, and 2) there is vast knowledge to be unlocked from non-professional sources. Illich might not have approved, but these insights could easily be applied within schools: older students could be recruited to teach younger learners, increasing personal attention without straining resources. Historically, children would have been educated with a diverse age range of their peers. That schools mono-crop by age is a bureaucratic preference, not one based on empirics, and could easily be improved without uprooting the entire system.

For Illich, the project of deschooling would “provide all who want to learn with access to available resources at any time in their lives; empower all who want to share what they know to find those who want to learn it from them; and, finally, furnish all who want to present an issue to the public with the opportunity to make their challenge known” (50). He suggests that an amendment be added to the Constitution guaranteeing the right to an education, implementing all of the above convivial institutions, and forbidding discrimination based on formal academic achievement.

Though it is rarely cited directly, Deschooling Society’s influence is visible in movements ranging from school choice to degrowth. Many of Illich’s ideas about cooperative and experiential education are convincing, but his state-skeptical leftism looks much worse after decades of neoliberal pruning and the failure of the internet to promote conviviality.

Significant learning does occur outside of the classroom, as Illich notes. Much of the point of school is just to warehouse children for working parents, and to keep juveniles from committing crimes (although Illich underrates how valuable these are in themselves.) He’s also right that children deserve broader access to public spaces, although the road to enabling that probably runs through urban planning, not education. It’s entirely plausible that an eight-year-old can learn more from running around in the woods or riding a train through a city than they would in a classroom.

If anything, Illich understates the damage done by the mass requirement of college degrees. Higher education derives its market value from two things: the hard skills it teaches, and the intelligence that a degree from a selective institution signals to employers. Both are, of course, subject to supply and demand—they derive their value from scarcity. Efforts to make all students go to college necessarily decrease the worth of a college degree, and cost resources that could go to ameliorating inequality directly, instead of through tulip subsidies. Education in the liberal arts is valuable in itself, but forcing every student who aspires to a white-collar job to complete a degree in Business is self-defeating.

Degree requirements are also cynically used to drive up wages for professionals at societal expense. For example, American students are required to finish four-year degrees before entering medical school, while their British counterparts enter immediately after high school. That Americans have worse health outcomes than nearly every rich country suggests that these extra years of schooling are not providing essential training, but rather serve as a filter to keep doctors scarce and debt-loaded. Licensing creep is beyond the scope of Deschooling Society, but it’s easy to imagine Illich opposing credential requirements for jobs like manicurists and florists as well.

Still, Illich’s optimism about the emergence of a population of autodidacts appears unfounded. His reforms were formulated in the early ‘70s, when the most advanced peer-to-peer communication technology was the telephone. Widespread internet access should have been the ultimate convivial tool, facilitating connection and unlimited access to information, and although it provides learning groups, skill exchanges, and reference services, it hasn’t reshaped the way society relates to education. It certainly hasn’t turned us away from consumption as a way of life.

Is the internet structured in a coercive way, or is conviviality simply limited in its transformative power? Illich might have claimed that the oligopoly powers of Facebook and Google have undermined its conviviality, and that algorithms are coercion in a kinder, gentler form. He might have also claimed that liberation must start with the abolition of school before conviviality can transform our social relations, but I’m doubtful.

I am, of course, chronically schooled, and write from that perspective; but I agree with Max Weber that “Democracy is all very well in its rightful place. In contrast, academic training of the kind that we are supposed to provide…is a matter of aristocratic spirit, and we must be under no illusions about this” (Weber, 6). Forcing 15-year-olds to read Shakespeare and The Catcher in the Rye is both worthwhile and implausible without some degree of compulsion. It’s not ideal that teachers act as therapists and moral authorities, but these roles are load-bearing: it would be neither desirable nor possible to give them back to the Church they were inherited from. Illich’s tools for conviviality, unless accompanied by a significant welfare state expansion, would not replace them.

Conviviality sounds appealing, but without meaningful changes in distribution, it wouldn’t have much power to change social relations. Even if one accepts the premise that transformed education would be utopian, Illich’s anarchist approach to implementation would only worsen societal fragmentation. It’s meaningful that wingnuts are overrepresented among Illich’s successors in the school choice movement. Yes, there’s a reciprocal relationship between teachers’ unions and liberal politicians, but public schools have been the venue of key reforms, most notably after Brown v. Board—reforms imposed by the state from above, but unambiguously good nonetheless. (Illich warns that a school choice policy that still requires formal education would only further the interests of segregationists and religious fanatics. He doesn’t discuss integration—notable in a book published in the early ‘70s—but it would be difficult to implement a bussing regime on a thicket of homeschools.).

And there’s good reason not to accept Illich’s premise. His “watered-down Marxism” should have imparted that social relations are built on economic relations, and that the superstructure will not meaningfully change without a change in the base (Martin 2002). A revolution in education might make people psychologically healthier, but it is a parochial retreat from a comprehensive left-wing project.

Illich was a brilliant theorist and an incisive critic of the state; unfortunately, the ‘60s and ‘70s were not lacking in either. In 2023, a lack of state capacity is much more threatening than state overreach. Teachers can’t act as moral authorities because parents and local administrators are empowered to strike even the most inoffensive speech from curriculums (Mehan & Friedman 2023; Somasundaram 2023). Climate change demands enormous public action, yet the environmental movement that inherits it was born in battles against urban development and nuclear power—trained to protect localities’ autonomy, no matter the collective costs (Reuters 2011). Wendy Brown’s critique of how the market shapes education in Undoing the Demos is much more useful than Illich’s inverse diagnosis.

If it’s easy to critique Illich today, it’s because his project was so successful: anarcho-liberal conviviality won against harder-left projects to become the dominant opposition of the last fifty years (Sunkara 2011); it was probably more cutting in 1971. Although there are specific insights about reciprocal, unbound, and holistic reforms to education that remain relevant today, the expansion—not the abolition—of public education should remain the goal of any serious progressive movement. If you want to become a rock iconoclast, the library might suffice; for the rest of us, schooling will have to do.

References

"Exclusive: Sierra Club Sues over California Solar Plant." Reuters, January 5, 2011. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-solar/exclusive-sierra-club-sues-over-california-solar-plant-idUSTRE70432N20110105/.

Illich, Ivan. 1970. Deschooling Society. London, UK: Marion Boyars, 1970.

Martin, Douglas. 2002. "Ivan Illich, 76, Priest Turned Philosopher Whose Views Drew Baby Boomers in ’70’s." The New York Times (New York, NY), December 4, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/04/us/no-headline-217891.html.

"Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools." PEN America. Updated April 20, 2023, accessed November 20, 2023, https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/.

Somasundaram, Praveena. 2023. "School Official Stops Dr. Seuss Reading When Student Raises Racism." The Washington Post, January 12, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/12/planet-money-podcast-seuss-race/.

Sunkara, Bhaskar. 2011. "The ‘Anarcho-Liberal’" Dissent, September 27, 2011. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/blog/the-anarcho-liberal/.

Weber, Max. 2004. "Science as a Vocation." Translated by Rodney Livingstone. In The Vocation Lectures, edited by David Owen; Tracy B. Strong. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 2004.